I’ve avoided so far writing a life story, except for the gardening part of it. Now I have to diverge a bit to the story of Claymont School for Continuous Education and how the inner training I received there—during a summer course in 1975, and during the September 1979 to June 1980 Fifth Basic Course—set me up for further training in Biodynamics and in gardening. All together I spent a year on that red dirt hill and, twice, it changed my life. The summer course made a hermit out of me [you won’t hear in this book about my seven months in the Nevada desert—no gardening going on there] and again five years later to set me on a quixotic course toward mastership in gardening.

It was a different era then. Today, when The Dalhi Llama and Pema Chodron are featured in the front of the bookstore and commuters listen to audio tapes of The Power of NOW, it’s hard to remember when teachings from the East were something outlandish, half fascinating and half freak show. The Beatles had their photos taken with the Maharishi and Ram Dass was at Lama Foundation in New Mexico writing Be Here Now. It was all beards and robes and smiling gurus, exotic as in not-to-be-taken-too-seriously. When Ram Dass was Richard Alpert and along with Timothy Leary was fired from the faculty of Harvard for experimenting with LSD, just 10 years earlier, I was in graduate school, in psychology too, and I thought he was crazy to give up bigwig status in his profession for a knuckleheaded notoriety. But by 1975, having been chastened and broadened some by life, I was ready for Be Here Now, for something…

The great and glowing promise of the Gurdjieff work is that it’s quick, made to order for the 20th Century American who just doesn’t have 40 years to spare, looking over his shoulder at the sun like a fakir, or to be obedient to an abbot, like a monk.

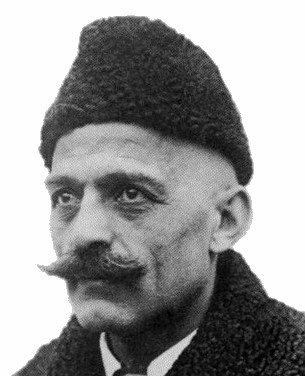

Mr. Bennett toward the end of his life ran courses at Sherbourne House in England to bring the teachings to a sampling of the younger generation, a few dozen at a time, mostly Americans as it turned out. In a 1974 document “Call for a New Society” he wrote:

Progress in self-perfecting is not automatic; it requires use of the right methods and the determination to persevere against all discouragement. Very few people can achieve it alone; and, for this reason, 'Schools of Wisdom' have existed from time immemorial to provide instruction and to create environments in which all can contribute to the common aim. Although such schools have always been present they are little in evidence except in times of crisis and-change, when they extend their activities to enable more people to prepare themselves for the task ahead.

We are now in such a period….

Mr. Bennett founded Claymont as a such a school to provide a series of nine-month Basic Courses, a kind of basic training in the manipulation of human energies. Claymont was also seen by Mr. Bennett and his colleagues as a venue for an experiment in intentional community that he pictured in A Call for a New Society. After basic training, we were told, we could go from there, taking away what we could of experience and technique toward gathering for ourselves what Gurdjieff called a “kestjan body,” a soul. This is not as outlandish as it seems, baldly presented on the printed page. We knew these promises were at least plausible, because of the very guilelessness of the presenters. Fourth Way people are not hard-sell artists, nor are they trained teachers. But they did carry a certain presence…

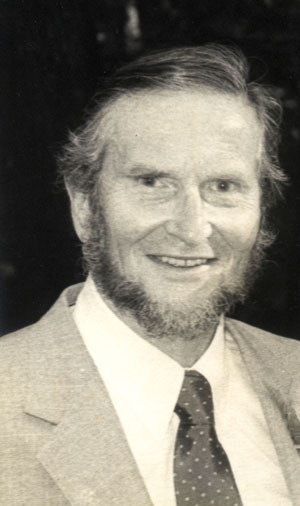

Pierre came to visit our group in Reno in the winter of 1975, looked us over, gave a little talk on what is called The Work, guided us in the Gurdjieff Movements [more about these sacred dances later], but engaged in recruitment talk not at all. I don’t believe it was even mentioned that a summer course was going to happen at Claymont in a few months. I have wondered over the years what Pierre thought of us, a ragtag group of unreconstructed hippies; Pierre, cultured and disciplined, graciously European, well-spoken and courteous—he must have shuddered at the prospect of having us for students. But he had assisted Mr. Bennett at Sherbourne House and knew that young Americans, some of them, were teachable.

WHO WE ARE

We are three-brained beings whose natural harmony of mind/body/emotions got severely distorted by culture and so-called civilization. We were better off before cities were invented and we are all victims of the long, twisted reach of culture. But however damaged and deranged we are by civilization, our role is to transform lower energies into higher ones. That’s what is required of all sentient beings. We can do it as an awakened human, embracing the conscious labor and intentional suffering in our lives; or we can do it asleep, enslaved by cultural conditioning and education, programmed like an automaton and dying like a dog, having missed our chance to grow up, to acquire a soul and move on past the cultural illusion. Either way we serve the moon, Gurdjieff teaches. That is to say our personal energies, sent out to the universe, help maintain Luna in her orbit. We can choose to live as a human and have the possibility of becoming more fully so if we are clever enough. This is not an article of faith. It is demonstrable, and exemplars came in droves that first summer at Claymont, presumably marveling over the audacity of the experiment. We had lamas and sheiks, Buddhist and Christian monks, dervishes and bishops and more sheiks. They arrived singly or in groups and once when a veritable symposium of them was meeting with Pierre Elliot in his modest home on the Claymont farm a thunderstorm raged for hours and we students wondered whether it was the landscape angels rejoicing or the powers of darkness unleashing themselves. Each of these exemplars taught a class or two, or led a meditation. Sometimes there were feasts and celebrations, often involving considerable drinking of vodka. However we met with these men—as I remember, it was all men—their holiness and wisdom shone through. Almost none were Americans.

WHO WE ARE NOT

We are emphatically not the “I” of the moment. Within us is a horde of small i personalities, clamoring for attention: “i’m the BIG I—look at me!”

That one, the one of the moment, the one that is cold, or horny or indignant, doesn’t even deserve to be capitalized. Temporary, changeable, fleeting small i … who cares? We live in a teeming huddle of small i mini-monsters feeding off the emaciated, un-cared-for core inside us, the only part of us deserving to be called an “upper case I,” our essence.

A RUMI POEM

come and see me

today i am away

out of this world

hidden away

from me and i

……….

i have no idea

how my inner fire

is burning today

my tongue

is on a different flame

i see myself

with a hundred faces

and to each one

i swear it is me

surely i must have

a hundred faces

i confess none is mine

i have no face

-- Ghazal 1519

Translation by Nader Khalili

"Rumi, Fountain of Fire"

Burning Gate Press, 1984

* * *

come and see me

today i am away

out of this world

hidden away

from me and i

……….

i have no idea

how my inner fire

is burning today

my tongue

is on a different flame

i see myself

with a hundred faces

and to each one

i swear it is me

surely i must have

a hundred faces

i confess none is mine

i have no face

-- Ghazal 1519

Translation by Nader Khalili

"Rumi, Fountain of Fire"

Burning Gate Press, 1984

* * *

All this is pretty abstract, and sketchy, but I can summarize some of what I took away from Claymont, especially as it relates to my education as a self-aware gardener. Remembering all the while that words are slippery and my Claymont experience was much of the time beyond words, ineffable.

In order not to preach any further here, and to return to my main theme, gardening, I shall sprinkle Snippet Boxes—you will recognize them in a different font—throughout the rest of this book. If these snippets seem impossibly jejune to you as a 21st Century reader, forgive me for bringing them up, for the things I learned decades ago at Claymont –terrifying as they were—prepared the ground in me to be a gardener….

- SNIPPET--ATTACHMENTS

- “Human beings are the only animal that can get addicted to ANYTHING,” Terence McKenna said. “Drugs, each other, the way we look…doesn’t matter, we can get attached to it…”

- And as any good Buddhist will tell us, the number and scope of our attachments are a measure of our misery. The more we have to lose, the more vulnerable we are. Ego attachments, emotional bindings, intellectual delusions, self image, self justification, self protection—it’s all gotta go, says our teacher.

- We were immersed at Claymont in a community life of household work, farm and forest stewardship, class activities and projects, Gurdjieff’s sacred gymnastics—calculated to wear away our personality armor, expose our self-centeredness and greed, our many-facades-all-of-them-false. Live in a dorm, cook for 100, and meditate your butt off. Be told by a fellow student, whose role today is House Supervisor, to re-clean a toilet, because your role today is Upstairs Maid.

- In the midst of all the self-doubt, personality abrasion, and sheer loathing of your peers that such a life encourages, if you’re doing it with some diligence, there is the chance to wake up for a moment here and there and be stunned by the glimpse of reality that is visible when the attachments are dropped…when we remember for an instant who we really are.

- It was just such glimpses that kept me there at Claymont.

- There were times when great efforts could be made, when limitations fell away and we were in touch with an inexhaustible source—always in the present moment when past and future were truly irrelevant.

One of the classes that first summer was run by two garden ladies, one of whom had been a student of Alan Chadwick at the University of California at Santa Cruz. Though he later let go of his teaching of the Biodynamic method, in the early 1970s he did teach the use of the Rudolf Steiner preparations, for garden and compost. At Claymont, the gardeners were applying the Biodynamic methodology, and they gathered some of us students on a July day in an area of the garden recently designated as the compost yard.

At the Claymont farm there were open-fronted stalls that had formerly housed prize beef calves. The manure was old and dry, but we transported it by wheelbarrow to build a long, wide pile maybe five feet high and twenty feet long, watering it down as we went. Twenty tons, more or less. So the garden lady, I’ll call her Linda, had 12 or 15 students there and she said, “Well, we’re going to apply these preparations here, put them in the pile.” She was vague [or I was slow on the uptake] about just why we were doing this…something about cosmic forces, harmony of energies, whatever. I was OK with that. The packets she had of these preparations, five of them, just filled the palm of her hand. Under her instruction we inserted the tiny parcels of herbs into holes we poked in the pile with little ceremony, tamping the damp stall material around—an ounce or two of them were supposed to have a beneficial effect on 20 tons of compost. OK.

Then it got weirder. Witchier. Linda produced a vial of foul-smelling brown liquid, twenty drops or so in there. She says it’s juice from valerian flowers and that we’re going to stir it for 20 minutes, and then spray it on the pile as a kind of protective skin. She upends the vial into a bucket of water and demonstrates. With a whisk broom she stirs the liquid vigorously, first counter-clockwise, creating a vortex, then reversing direction, destroying the vortex and creating another, clockwise one. After a couple of minutes’ demonstration, each of us in the group took a turn, When it came to be my turn with the stirring I was less skeptical than I might have been. Something was happening, I knew.

We were taught at Claymont to focus on the present moment and our inner experience within the NOW. I stirred with some enthusiasm. The fragrance of those few drops of valerian wrapped me as I bent to the task and I got the knack of it quickly. The whisk goes faster and faster as more of the water takes up the momentum and finally the vortex is complete. You can see the bottom of the bucket and the top edge of the whirlpool threatens to spill out. Then reverse, quickly, and chaos ensues. Then a slow rotation in the new direction and gradually the water takes up the motion and the opposite vortex develops. I was enthralled by the energy thus created and lapsed into a profound meditation, drawn in by the valerian solution. I could feel the power of it, the potency.

Years later Barbara, my beloved, would say, “You’re the only person I know that can have an orgasm stirring the preps.”

Others took their turns stirring and then it was done. We poured half of the solution into a hole in the compost pile and used the whisk broom to flick the rest of it onto the pile, scattering the droplets evenly over the surface. As I participated and watched I came to an understanding, complete and whole as it arose: “THIS is what I’ve been missing in gardening…the element of spirit, the enlivening dynamic of human intent.”

Well, all right…that last bit is bogus. Those are the words I write three decades later to describe the unutterable experience I was having. Intuition was aroused…a dim remembrance was evoked, not of the childhood farms, but of lifetimes further back, my peasant days. I knew that I knew deep in my being how to do my part to bring forth fertility. It rang in me like a chime--in the vortex was an understanding, in the flower essence was a force that my own intention could ride into the future, into the crops this compost would feed, and the people…in the garden next year, when I was gone. When I was gone, the intention would still be active and potent even so. We’re working in non-material realms where there is no entropy, no deterioration. An effort, once launched, is forever.

In an instant I understood compost. Years later I would teach, “There is no garden problem that isn’t solved with compost…righteous, cow manure-based Biodynamic compost.” Insect problems? Grow strong, resistant plants in well-composted soil. Disease? Ditto. Soil won’t drain? Compost will loosen it. No organic matter…sandy…infertile? Compost…compost…compost.

Two themes recur in my gardens over the decades. Compost stories and greenhouse stories. Whatever else I may have done to feed folks, I always left behind a greenhouse and a compost pile, and garden ground more fertile than when I came.

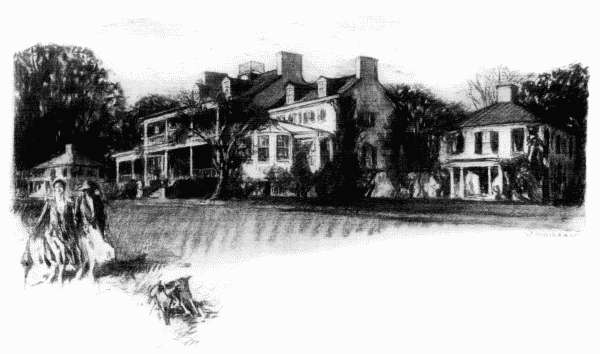

The Claymont Court property, 300-some acres, well watered and in many places heavily forested, was developed by a nephew of George Washington in the 1820s. The mansion at the top of the hill was dilapidated when we arrived in 1975, but still elegant. Separate small buildings, slave quarters, flanked the main house with its formal dining room and ballroom and verandas front and rear. I know nothing of the human history of the place beyond that it was said to be owned for several decades in the early 20th Century by people who built up a famous herd of Hereford cattle. This was evidenced by the fact of The Great Barn, a two-storey, 400-foot long concrete block structure with a huge octagonal show arena at one end. It was this building, I’m convinced, that sold Mr. Bennett on the place, for, renovated, it would make [and indeed did make] a wonderful school building.

This conversion—from a huge structure designed to house large animals and their hay, into space for human habitation [commercial kitchen, dining and meditation rooms, offices, bathrooms, sleeping rooms for 100, windows, heating plant, raising the roof to provide headroom on the second floor]--was in the process during the summer of 1975, with a crew of expert architects and tradesmen, all students of Mr. Bennett’s, us, their student helpers, and a very large pot of money—from where I do not know. Between mansion and barn was a shaded two rut road a half-mile long passing by several of the farm staff houses. The oak trees at Claymont were astonishing: monumental trunks supporting many low branches extending horizontally to the ground for 25 or 30 feet, as big around as the trunk of an ordinary tree. One of these would shade a mighty convocation of elves, and perhaps they did. The night before we arrived in June, 1975, there was a terrific thunderstorm and everywhere there were fallen limbs and even toppled trees. A couple of weeks into the course, my roommate Slow Bob and I skipped lunch to do a bit of unasked-for work, sawing up some limbs for firewood. We were feeling good about ourselves, cutting away with light bow saws, working up some righteous virtue when Pierre, also skipping lunch it seems, walked by on the driveway and, a few minutes later, back toward the mansion. He didn’t acknowledge us at all, but I knew he’d seen us and my self-congratulations were running high when the saw blade jumped out of its kerf and a single sharp tooth sliced through my left thumbnail, right from bottom to top and blood welled from the wound. I saw this happen in superbly choreographed slow motion, in vivid detail, flabbergasted and delighted before the pain hit, for I knew that Pierre had gifted me with a taste of real consciousness, of grace, baraka.

Claymont was set up as a School of Life, an education and a tour in the landscape of soul. It was an experiment in community living with opportunities a hundred times a day to face up to your shortcomings, reflected back to you from the people you lived with, and to rise above yourself to serve the land, animals, and fellow travelers on the path. If I failed to profit from some of the opportunities there were still others of them to meet, all day long every day. Pierre Elliot and his helpers, with Mr. Bennett’s blessing from the grave, set up the conditions for people to rub against each other and glow in the friction of it all. In the nine-month Basic Course 100 of us students lived, with quite a few other people, in a single long, low building with dorms and private rooms, communal bathrooms, meditation room, theater for sacred gymnastics, dining room for 120, and a commercial-scale kitchen. Everybody was expected to do everything: cooking for the whole group, baking 24 loaves of bread at a time, stoking the boiler, gardening, animal tending, child care. Learning new things was part of the deal. We were jolted out of the comforting routine of existence, of doing our best, but only at the things we do best [which is the way we would choose to operate], and subjected to trials by fire, with lots of self-doubt, performance anxiety, and failures.

Last night, as I was sleeping,

I dreamt—marvelous error!—

That I had a beehive

Here inside my heart.

And the golden bees

Were making white combs

And sweet honey

From my old failures

--Antonio Machado, Times Alone

I dreamt—marvelous error!—

That I had a beehive

Here inside my heart.

And the golden bees

Were making white combs

And sweet honey

From my old failures

--Antonio Machado, Times Alone

We may never be more awake, I came to realize, than when we’re learning to do new things and Gurdjieffian schools have always set up conditions to compel people to live in unaccustomed ways, eating new and sometimes ill-prepared food, working in woods and field and cleaning bathrooms, sleeping in a room with half a dozen others, none of whom love you. All these conditions rouse us from our normal state of comfortable slumber and egoistic self-regard.

My specialty during much of the nine months was not gardening but rather caring for the pigs.

Here’s how that came about. We often had quick morning meetings on “House Day.” Our group of 80 students was divided roughly in thirds and the Claymont schedule provided for one-third of the group each day to do the housework, which included child care. In the first week I’d involved myself with that, only to discover that however adept I thought I was at taking care of two-year-old Sky, my son by default as I’d not yet adopted him, and another 6 or 8 toddlers and preschoolers…this was all beyond my ability to cope, even if I did have partners in the job. They were a mighty force for chaos, those little ones—quite beyond me. So in this morning meeting on the second house day I was intrigued when one of the farmers showed up recruiting for pig duty. This was a different kind of assignment Patrick told us, as it involved a commitment for the entire nine months; the pigs are sensitive critters, he averred, and could not tolerate different keepers every day—they needed continuity of care by the same dedicated bunch of swineherds. This meant that I would not rotate around to child care duty on house days, ever again. I stayed after the meeting with a few others to learn more. The other 20-some students left quickly to their bathroom and kitchen and kiddo duties, slipping out the door away from Patrick’s noticeable effluvium.

He took us outdoors, where the pigpens were conveniently located close to the kitchen and the tofu factory. We toured the extensive swineland with Patrick, who introduced us to the brood sows, more than a dozen of them separately housed within plank pens, each with her own shelter, mud patio, feed and water containers. Some were awaiting a birthing [Patrick knew all their due dates by heart], others were accompanied by a litter of piglets. A couple of boars had their own quarters as well, sturdier by far. Other pens held weanling pigs and their elder brothers and sisters. Altogether, this was an impressive facility to a farmboy wannabe like myself—dilapidated to be sure, like much of the rest of the Claymont grounds. Mansion, houses, and the Great Barn where we lived had not been inhabited for forty years before the school took it over five years before. Much had been done toward renovation, but the swine complex had not topped the priority list.

Did I want to sign on as a swineherd? You bet! Did I care that I would be asked to hang my overalls outside the dining room on pig days? Nope!

For the rest of the fall, winter and spring I tended the sows and their numerous offspring. I helped to dig a two-hundred yard trench for a waterline to an outlying pig pasture, went to the livestock auction, either with pigs to sell or to find pigs to buy. I carried the tofu dregs and kitchen wastes to my pig friends in dozens of 5-gallon buckets, slopping through the mud, righting feed troughs that had been played with by 500-pound sows. I fixed fence endlessly as piglets found the holes. I loved it all.

I took on the laying hens as well, a couple of hundred of them, and the moments of animal tending were the anchors in my day. While very many things at Claymont evoked confusion and bewilderment and frustration aplenty, my times with the chickens and pigs made sense; fill the waterer, fill the feeder, shovel shit, observe the scene, observe the self.

SNIPPET--ASK THE TASK

I never heard anyone at Claymont put it quite like this, but Ask The Task was my personal code when I was upset or confused and not knowing what to do. Very simple: ask the task in front of you what’s needed. Maybe a sink full of dirty pots and pans. It’s house day, every third day for your group, and your role is Kitchen Boy. “Why…but I’ve got a PhD! Shouldn’t I be giving a seminar?” Forget it…you’re kitchen boy. So you’re upset [that is, ego deflated] and confused [“What have I got myself into with this stupid Claymont place?”] and Ask The Task pops up.

“Oh. Dishes. Here they are and here I am.” And you do the dishes. Ask ‘em. How do they want to be done? Done well, of course. And so you apply yourself to the sink and the suds and have some peace for a while from the silly churnings in your head and heart.

I never heard anyone at Claymont put it quite like this, but Ask The Task was my personal code when I was upset or confused and not knowing what to do. Very simple: ask the task in front of you what’s needed. Maybe a sink full of dirty pots and pans. It’s house day, every third day for your group, and your role is Kitchen Boy. “Why…but I’ve got a PhD! Shouldn’t I be giving a seminar?” Forget it…you’re kitchen boy. So you’re upset [that is, ego deflated] and confused [“What have I got myself into with this stupid Claymont place?”] and Ask The Task pops up.

“Oh. Dishes. Here they are and here I am.” And you do the dishes. Ask ‘em. How do they want to be done? Done well, of course. And so you apply yourself to the sink and the suds and have some peace for a while from the silly churnings in your head and heart.

I also took on the tools. Anyone who has lived and worked with others can picture the scene in the Claymont tool shed. In my experience people who have not been specifically trained to do so almost never clean tools, sharpen them, or put them back where they belong. Here in the tool room was a jumble of landscape and gardening tools, all the shovels and hoses, piles of axes and saws for forest work, bill hooks, scythes, old-time tools, broken tools—dozens of them—dull tools—all of them. Lost tools—many of them. Misplaced tools—most of them.

One at a time I dealt with the tools, sharpening them, reattaching handles, smearing linseed oil on wooden parts, organizing them in their shed, cleaning out the junk. This was a wholly satisfying job and gave me a place to hang out other than my dormitory room which held a dozen other jerks like me, each more addled than the next.

Often in the winter I did my work with the tools in the boiler house, just a few steps away from the tool shed, where the person on boiler duty fed the fire box from the pile of firewood just outside. If I was sharpening and setting the teeth on a bucksaw or felling saw s/he would obligingly test my work. I was always touched that they were so amazed to experience the difference between a dull saw and a sharp one.

With the animals and the tools I managed to create my own core curriculum at Claymont. I attended all of the scheduled meditations, most of the meetings, almost all of the classes and lectures, all the readings, all of the work sessions. What I skipped, and I’m ashamed to say this, was the one offering of the Claymont teachers that they considered most important: what are called Gurdjieff’s Movements. G. I. Gurdjieff often preferred to be called, simply, “a teacher of Temple Dances,” and judging by the emphasis placed on them at Claymont and in the many memoirs of students, the dances were a crucial part of his teachings. Maybe the most crucial. From the beginning of my involvement with this Gurdjieff stuff, months before Claymont, I was bamboozled, bewildered and baffled by the Movements. Our teachers in Reno did their best to teach our small group the First Obligatory, a puppet-like series of arm, leg and full body positions assumed to a dirge-like piano accompaniment, positions to be taken with no waste motion and with complete precision, not like a robot but like a conscious human being. That means between the time the arm is extended, say, directly in front of the shoulder and the time it is again at your side, just so…no time elapses, there is no lag, there is no delay in the synapses, there is no transmission time from brain to muscles. Movements training involves exquisite harmonization among the head-brain [presumably in charge of intention and attention], the heart-brain [of devotion and motive], and the body-brain [all the workings of the nerves between the spinal cord and the muscles.]. This balanced state results in Movement demonstrations [there’s one at the end of the film Meetings with Remarkable Men] that show uncanny performances by experts. Of 100 people who try the Movements, probably 20 or 30 get fairly good at it, good enough to perform in demonstrations; another 5 or so might become good enough to teach. I was at the other end of that curve. I was so bad at this body-heart-brain co-ordination that Movements classes were an agony of self-reproach, nay, self-loathing, and the more I indulged in this negativity, the worse I got. Finally, in the winter of the Fifth Basic Course I quit altogether. If anyone noticed, no-one said anything, and certainly there were no consequences. When everyone assembled on the giant hardwood dance floor in the Octagon, I absented myself, not to goof off, but quite conscientiously to my tool work, or to the garden.

At nearly 40, and never having been the sort of guy who thrives under rules, I felt I could admit failure with the Movements, quit beating myself up about it, and at least in this one thing write my own program. Possibly Pierre noted that I’d done this and possibly someone told him, but there was never a comment. Maybe nobody ever noticed.

* * *

Every afternoon during the course, in the hour before supper, Pierre read to us from Gurdjieff’s massive work All and Everything: Beelzebub’s Tales to his Grandson, An Objectively Impartial Criticism of the Life of Man. The book is full of neologisms, awkward expressions, prolixity, twisted myth and conjured allegory, purporting to be the history of mankind on our planet as told by the exiled devil, now on his way home to the center of the Universe after having been pardoned by our Endlessness, God. Gurdjieff went to great lengths to make it difficult to read and understand the book, and for us students, at the end of a day of hard work and study, the readings were alternately bewildering and soporific, creating a hypnogogic state that may have helped us to absorb some of Gurdjieff’s intention. In his study of Beelzebub J. G. Bennett grapples with the contradiction of trying to explain a “book that defies verbal analysis” and concludes that Beelzebub’s Tales is an epoch-making work that represents the first new mythology in 4000 years. He finds in Gurdjieff’s ideas regarding time, God’s purpose in creating the universe, conscience, and the suffering of God, a synthesis transcending Eastern and Western doctrines about humanity’s place in the cosmos. OK.

One afternoon Pierre didn’t show up. The thick book rested there on the rug where he usually sat crosslegged to read to us and there we were, ranged along the three other walls, waiting. Five minutes…ten. No Pierre.

I usually sat in the corner of the room at Pierre’s left and on this occasion I sidled over to his place, found his bookmark and began to read. I stumbled over some of Gurdjieff’s singular renderings of the language from time to time and repeatedly mispronounced the word elucidate as ee-LUD-i-cate, as one of the students pointed out afterwards, but made it through the rest of the session to the supper bell. Pierre never did come and, again, I never knew if he

This sort of thing was one of the features of life at Claymont. We were often faced with challenges quite beyond the ordinary craziness of community in such a setting. Another example:

Every month or so there was announced a “feast,” often, as I have mentioned, on the occasion of a visits from sheiks and other highly evolved persons, or on Gurdjieff’s or Mr. Bennett’s birthdays. The dining room had the picnic-type tables removed and the benches were lined up end to end to form low tables. Tapestries, Turkish rugs and cushions were hung and scattered on the floor for guests.

The food prepared for feasts was always a cut above the daily fare. For one such feast during the summer course my old friend Lynda was head cook and I was sous-cook and in the mid-afternoon one of those spectacular thunderboomer storms came through the landscape, rattling our nerves even more. Then the electricity went out, common enough during these events, but crucial for us since the mansion kitchen featured just two decrepit electric ranges and we were cooking for 100 people. [The Great Barn kitchen was not yet ready; the workers were just then raising the roof of the hay mow to provide head space up there for dorm rooms.] We waited a bit, hoping the lights would come back on, while chopping vegetables in the darkened basement kitchen. Nothing.

Finally, determined not to be rendered helpless in front of a 20th Century difficulty, we checked the draft of the mansion ballroom fireplace with a wad of burning newspaper, found that it was OK, and I went to find firewood. Before long we had a nice fire going and big pots of water in the coals to boil. They were just getting going when…the lights came back on.

Now, the question: Did someone flip the switch on us? Was this a cunning plan of Pierre’s to push the cooks to the brink? We’ll never know. We do know, however, that the conditions of life at Claymont were designed to awaken us from our habitual sleepwalking state, to push us into what Gurdjieff called “self remembering.”

SNIPPET--Being and Doing

We are doers, we Americans. We pride ourselves in getting things done. Like Thoreau’s farmer we carry our accomplishments on our backs [the farmer carries his barn and livestock]. What we present to the world, masquerading as our selves, is our accumulated deeds and possessions [all bought with our doing], the personality that exults in our performance and seeks recognition for our activities. We mistake activity for progress while hiding from everyone the tender essence that’s been larded over by our attitudes, interests, desires, behavior patterns, emotions, roles and all the traits we identify as self. The real kernel of selfhood inside all that blubber, we were taught at Claymont, is our spark of divinity, it’s what stays the same, our inner child. It’s still a child, when we are in our middle years, because we have let the culture around us reward our doing, while trampling on our being. This has been going on s, since childhood. If being were to be nurtured, if the inner child had been allowed to grow robustly, we would not be the deluded, smug, pretty specimens we are. If we dare to seek the good of our essence we will welcome any assault on personality, anything that peels away some of the suffocating layers of culture and ego and lets the sun shine on that child in there, give it the attention it deserves. We might dare to put some real effort into project of being.

Being still. Being real. Being wholly human

How to do this? Well, I’m thinking that’s why I went to Claymont.

We are doers, we Americans. We pride ourselves in getting things done. Like Thoreau’s farmer we carry our accomplishments on our backs [the farmer carries his barn and livestock]. What we present to the world, masquerading as our selves, is our accumulated deeds and possessions [all bought with our doing], the personality that exults in our performance and seeks recognition for our activities. We mistake activity for progress while hiding from everyone the tender essence that’s been larded over by our attitudes, interests, desires, behavior patterns, emotions, roles and all the traits we identify as self. The real kernel of selfhood inside all that blubber, we were taught at Claymont, is our spark of divinity, it’s what stays the same, our inner child. It’s still a child, when we are in our middle years, because we have let the culture around us reward our doing, while trampling on our being. This has been going on s, since childhood. If being were to be nurtured, if the inner child had been allowed to grow robustly, we would not be the deluded, smug, pretty specimens we are. If we dare to seek the good of our essence we will welcome any assault on personality, anything that peels away some of the suffocating layers of culture and ego and lets the sun shine on that child in there, give it the attention it deserves. We might dare to put some real effort into project of being.

Being still. Being real. Being wholly human

How to do this? Well, I’m thinking that’s why I went to Claymont.